The Year of Remembering Arduously

— Rifki Akbar Pratama, researcher and a member of KUNCI Study Forum and Collective.

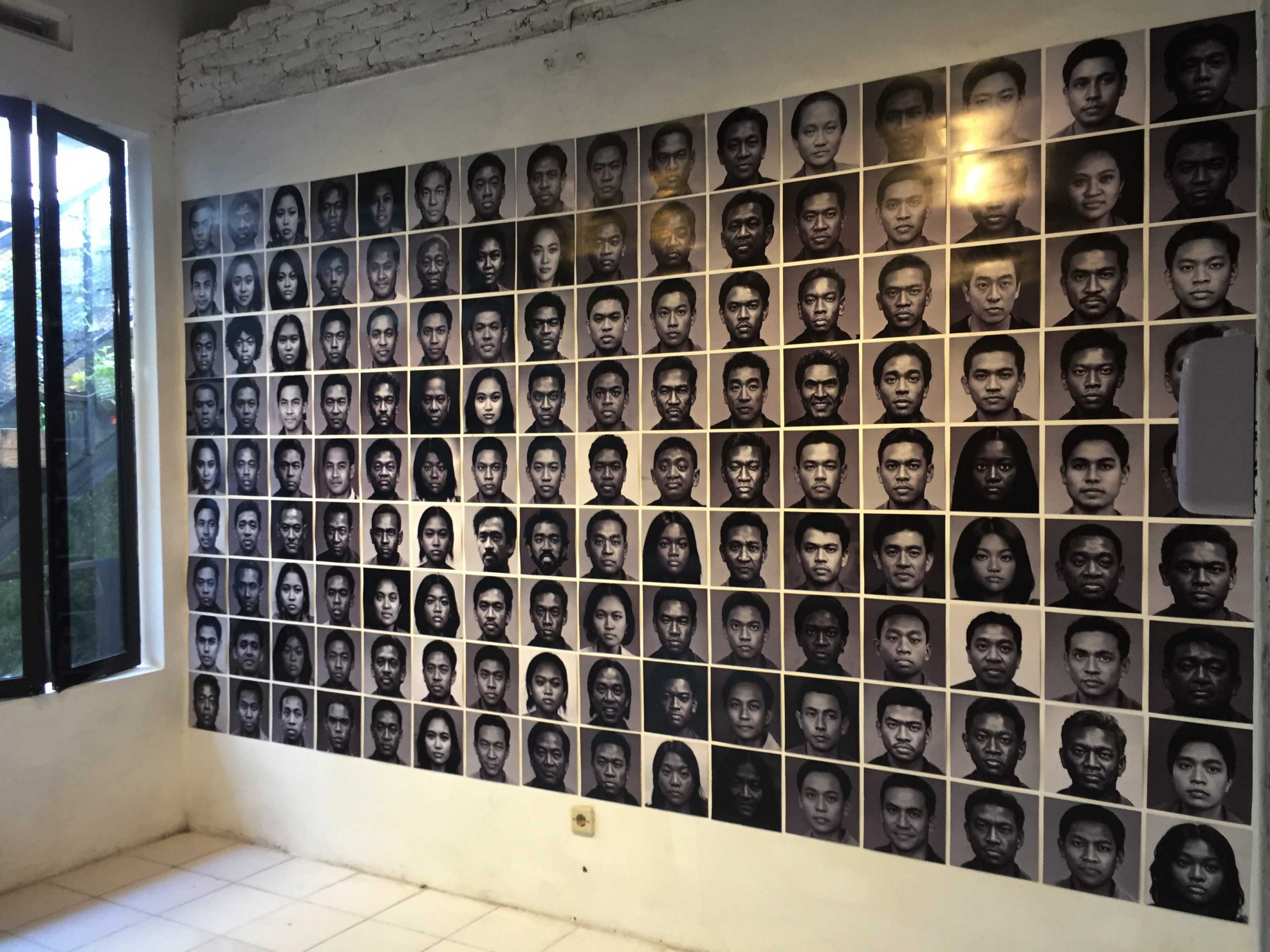

Two hundred and eighty-eight faces were staring at you to and fro, mugshot in black and white: some may look charming, some may seem odd, some may look alike, and some drive you to assume that you recognize them as a distant relative or a familiar person. One thing for certain: none of the latter stated is possible.

Any resemblance to real persons, living or dead, might be purely coincidental, and there is no element of intent. All faces appearing in the photos are born out of speculation in light of machine learning. Speculation concerning the faces of the victims of the anti-communist purge in 1965–1966. The made-up faces were a part of a more profound inquiry by Rangga Purbaya’s solo exhibition entitled “Tahun-Tahun Yang Berbahaya” (The Dangerous Years) at Ruang MES 56.

The gaze from these faces uncannily raises several questions. Who are they? What stories will they tell us? What kind of situation brought them to be depicted in the same manner? Another set of questions will arise if we linger longer. However, amid the expanding inquiries in the exhibition, one question is looming at large: how do you sympathize with a person with whom you share no past?

For some visitors, perhaps keywords such as the “First of October Movement” or “the ’65 tragedy” written on the wall text will tie these faces with a particular context. It will seamlessly offer discourse about the crimes against humanity and mass murder as the issue at hand. At the same time, the exact keywords will bring nothing to the mind of other viewers – the mind of the people who have never been exposed to the history of the ’65 tragedy. The identical situation equally happens to the mind of people who have solely been exposed to the official state version of history. They will see these photos only as a bunch of nameless faces.

The nameless faces pushing the reflection on the Indonesian killings of 1965–1966 further compared with his last work, Figuring Misfortune (2022), where the AI-generated figure is being named. It also adds complexity as it brings up the aforementioned question. By the time you read this, the people who are imagined to remember the nation’s dark history have also become younger. There is no immediate memory about the victim or survivor held tight by this later generation. There are no particular feelings toward the victims or survivors that sympathy can gravitate to.

The absence of immediate sentiment toward the victim’s story provides an interesting point of reflection here. Instead of sympathy, it gives rise to certain feelings of perceived distance. In the age of social media, the methods of presentation chosen by Rangga brought the issue of context collapse to the fore. Context collapse, the moment when our message can reach endless people without a precise context it initially refers to, emerges alongside these nameless faces. These faces might allude to the dark history for a person who knows the history of the ’65 mass murder but not to people with historical blindness. As counterintuitive as it could be, it brought to the audience, to a certain degree, a feeling of cluelessness. Instead of conviction about certain truths — that context collapse brings in the age of Twitter and bolsters up a self-righteous attitude — these unidentified faces lead us to curiosity.

In talking about complex historical events, this feeling of curiosity is noteworthy. It brought the need for craving out more information. Out of five different methods of articulation in “Tahun-Tahun Yang Berbahaya”, only these nameless figures brought a new way of presentation apart from being presented as it is. The other works still need this creative vigour. The series of books in one room, either photocopied or original copy, will hint at how the historical discourse was harshly banned at a certain period. The military documents about the 351 people who were killed in Cluring, Banyuwangi during the periods might touch upon what Jess Melvin dubbed as the “mechanics of mass murder”.

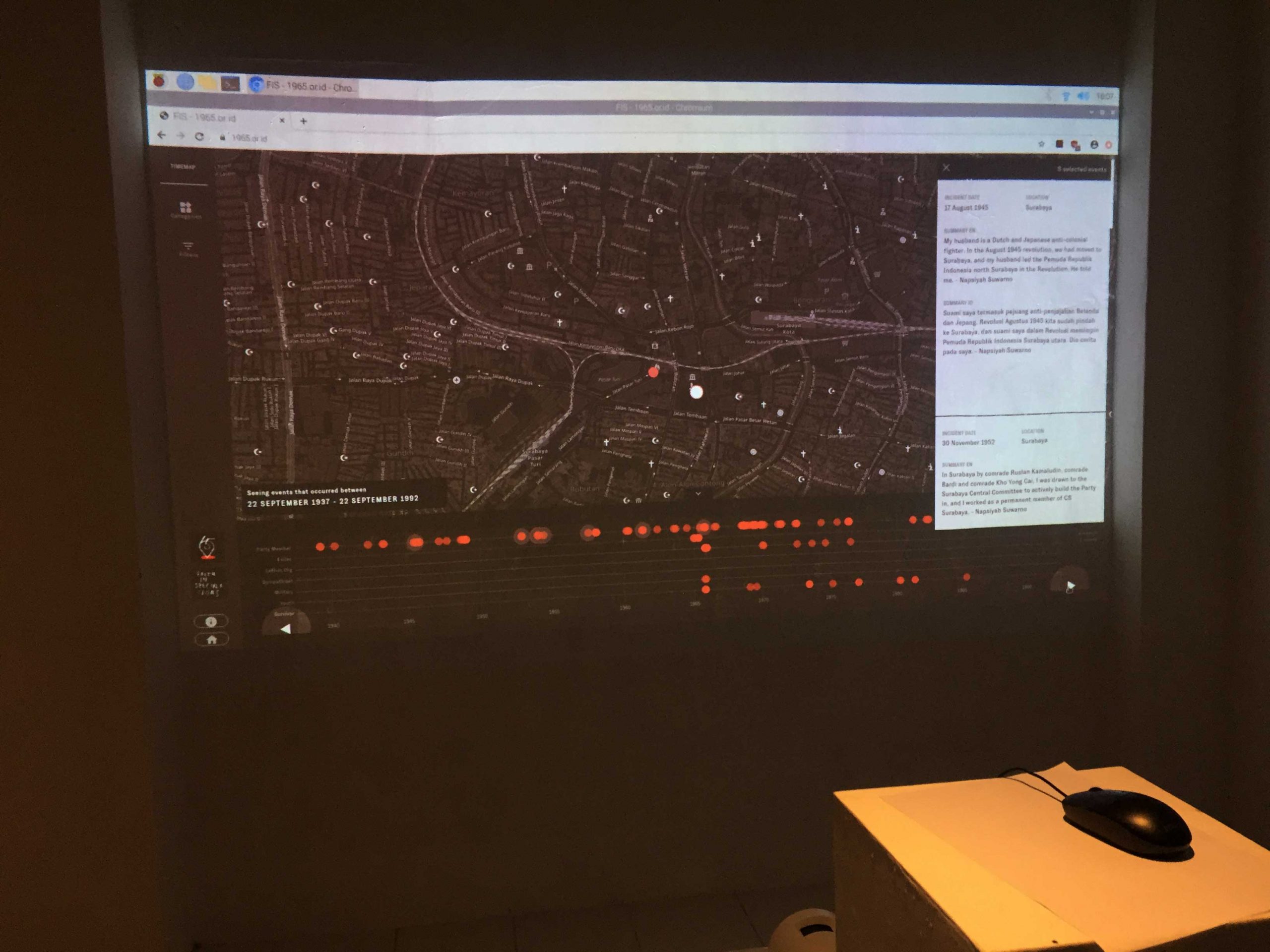

The fis.1965.or.id — an interactive crowd map with stories patched to — and the 57 minutes-long voice recording of Anton Lucas with a survivor of the 1965’s killings entitled “I Am a Leaf in the Storm” might call people to read and listen. Those, without a doubt, are important stories, but how they are presented does not bring any sense of urgency to drive people to know more. It might be pressing matters, but hard to be remembered. It might make a great effort to prove a point and, simultaneously, miss the point.

Survivors of the ’65 event have known these familiar stories. For years they must defend themselves armed with the idea of flawless fact because their stories are never believed. They need to present the facts as it is. No hearsay is accepted. They are forced to take the inverted plot of the boy who cried wolf. When they need to tirelessly state that their testimony is truthful, only to accept all of it eventually disregarded by the state. They need to show hard evidence, but at the same time, their stories are hardly heard at all. The state hardly counts in their stories as evidence.

The reason often used to justify this act of belittling is that survivor stories are bound with trauma. Every little detail that they said was dismissed. Every little piece needs to be tested for credibility, coherence, and consistency. They need to, again and again, retell their stories. They must actively interpellate the idea of putting themselves as victims. As long the pattern does not change, neither does the re-victimization. The same situation will repeat itself as long as their stories are considered unreliable. The act of stating the fact in parallel betrays the status of the fact itself.

In conjunction with trauma brought into focus, things get more intricate because trauma is perceived as highly unrepresentable. In the context of Indonesian contemporary art, this problem of representation often hinders artists from working with the issue concerning ’65 events. The risk of discussing this topic drives some artists to delve into “indexical arts” such as photography, film and video in order to produce “a truthful representation of events” and make the viewer bear witness. These well-intentioned efforts, unfortunately, are accompanied by complex unintended excesses, namely traumatropisms.

As long as the viewer of the artwork is exposed to a certain fact as it is – which was perceived as tied to traumatic events – they are destined to be secondhand witnesses. Consequently, the victim’s testimony is considered inviolable, hence the exact situation where traumatropisms occurred, as dubbed by Dominick LaCapra, when “transfiguration of trauma into the sacred or the sublime”. If this point of view is held firm, as LaCapra also stated, “In any case, it is misguided to see trauma as a purely psychological or individual phenomenon.” Simultaneously, it “diminish or even eliminate the causes of historical traumas often stemming from extreme differences of wealth, status, and power that facilitate oppression, abuse, and scapegoating with respect to class, gender, race, or species.”

Understandably, this indexical approach is chosen to keep in touch with survivors and their stories. As Hal Foster remarked long ago, concerning the art of real events, this type of turn to archive usually preferred to engage with neglected historical events. The problem with this bare-bones presentation is that the viewer might be emotionally stimulated but simultaneously experience distancing from the survivor’s experience. Since the beholder is given a passive role, the survivor becomes essentialized – they get revictimized. Thus, no agency was found in the role of viewers or survivors. The potential reparative role of witnessing is then amiss. As Susan Best has remarked, “To understand the reparative role of witnessing, however, the feelings of guilt and shame evoked by histories of injustice and inequality need to be considered.”

Confabulatory, where fact meets fabrications, as shown by Rangga with the nameless faces, is a fresh way to deal with the problem at hand. It brought new context to reflect on as it not only offers the fact as it is. To some extent, the aesthetic qualities of the images also shrug off the “positivistic obsession with objectivity and fascination with the political history of the central government”. Furthermore, just like oral history do, as also voiced by John Roosa and Ayu Ratih, it indicates an “incentive to write social history” and not only rely on written materials. In short, with the nameless faces, Rangga put to work critical fabulation – to borrow Saidiya Hartman’s term – and made the stories of the survivors enticing to be known.

Amid fascination toward artificial intelligence that proliferates in the contemporary arts, AI-generated faces presented by Rangga also indicate a critical distance to this festivity. A statement akin to what was put forward by Jaron Lanier and Glen Weyl, “AI is an ideology, not a technology”. In the hands of Rangga, AI is not a tool to exercise and ensure control over everything in the making. As the nameless faces present before us, they warn us fairly about who made up these faces and by what category they created. This matter is often ignored in the mirage surrounding how AI is grasped – the omission of the people who fed the data and categories the algorithm tries to learn. Additionally, the nameless faces Rangga shows also point us to a critical contemplation of how these faces will be identified.

As the survivor of the nation’s dark past knows, their lives are tightly bound to their symbolic body – the forced identity like “eks-tapol” (former political prisoner) stamped on their identity card and the like by the state. The mind of the flesh might be dead, but the data is forever. The same logic of registering is shown in “Tahun-Tahun Yang Berbahaya” through the displayed military document – to be named means to be killed. The non-representational method from nameless faces chosen by Rangga puts uncanny juxtaposition and dodges the very same trap. If the document show names without faces, Rangga puts it the other way around with the nameless faces. Since the faces are not to be named, it does not move toward being registered or identified. In short, we could talk about them without putting anyone at risk.

This degree of not knowing is a precious exploration to be noted. The opaqueness offered by Rangga through the nameless faces creates the need to seek it out. It puts the artworks in the middle between two silencings that hinder aesthetic reflection: the silence of the fully known and the silence that comes from the entirely unknown. A similar reflection was put by Martin Seel in ‘Aesthetics of Ignorance’, who stated that the aim of the artwork is to provide “opportunities for encountering what is indeterminate in what is theoretically and practically determinate.” The given opaqueness also help evades the trap of identity politics. This aesthetics strategy was valuable to be explored. To find a way not to shove ready-made stories but to nudge people to ask a question, to encourage inquiry, to encourage participation.

The perceived distance itself is not something that needs to be condemned. It brings a nagging sense of unknowing. It becomes the counterpart to modes of aesthetic registration – to count someone in and to name them – which can also be the modes of erasure. We need more witnesses in the near future, not only testimony that weighs on the survivor. As Hampate Ba already forewarn us, “old person dying is a library on fire.” It is critical for the stories of the survivor of the dark past to stay alive in the minds of the people, in the minds of the younger generation – as an unsettling curiosity. Rangga Purbaya’s experimentation to tell the nation’s dark past provides us with the figure. It is our part to put it in a certain context. It is our part to figure it out.